Vectorized Computations and SIMD

Recently I’ve been searching for ways to improve the performance of my never-to-be-released roguelike game. I make it in my spare time purely for the sake of programming and my own entertainment, so I often diverge into performance-related bikeshedding. This time I stumbled upon vectorized computations and SIMD to speed up some array-based algorithms in the game.

Before diving into the topic let’s try to come up with the simplest problem we could apply this solution to.

Problem

For the sake of demo I try to keep things as simple as possible. Imagine we want to sum a bunch of numbers. That’s what we do every day, right? Ok, maybe not, but it’s a good example to demonstrate optimizations that vectors can provide, you might be surprised in the end. Besides, making fast things even faster is always fun, isn’t it?

Naïve Solution

How would we approach the problem? Perhaps you already wrote some code in your mind. Chances are it looks quite similar to this:

public static int NaiveSum(int[] array)

{

var result = 0;

for (var i = 0; i < array.Length; i++)

{

result += array[i];

}

return result;

}(Another option would be using LINQ by writing array.Sum(), but as you might know when dealing with arrays LINQ might not be a very good tool as it brings the whole IEnumerable infrastructure along. In this case, exposing the enumerator and checking for the next available element make things slow.)

Writing production-ready code, we usually stop here as this solution is just good enough in nearly all cases. However, sometimes we really need to gain some speed preferably without plunging into a swirl of unmanaged code. Let me introduce vectorized computations.

Vectorization

Vectorization, in general, is a term for applying operations to a set of elements rather than to a single scalar element. That is, instead of doing:

8 + 13 = 21

76 + 19 = 95We do:

(8, 76) + (13, 19) = (21, 95)Combining elements into a vector and replacing two operations with one.

Modern processors can do a quite similar thing that’s called SIMD, which stands for single instruction, multiple data. SSE (Streaming SIMD Extensions) that implements this feature is an instruction set extension that was introduced by Intel in their Pentium 3 processor in 1999. It allowed programmers to operate on vectors containing 64 bits of data producing a result of the same size. That is, we could fit two integer values, each having a size of 32 bits, into a single vector.

Over time every new processor model brought along a more powerful extension: SSE2, SSE3 and so on. Nowadays modern CPUs have AVX (or Advanced Vector Extensions) allowing to operate on vectors that have a size of 256 bits.

The approach of doing parallel computations on a single core is not new for other programming languages, but in our .NET world it has appeared starting from .NET Framework 4.6 in 2015.

We can reach the SIMD-enabled types through System.Numerics namespace. Even if our hardware doesn’t support SIMD instructions, the types provide a software fallback. The type we are most interested in is Vector<T>. Its size depends on T. Since we only have 256 bits at our disposal we can pack 16 bytes, or 8 ints, or 4 doubles into a single vector.

Before we go any further with our demo problem, let’s explore how vectors work under the hood. We will write a simple example in which we add together two arrays containing 8 integers:

var array1 = new[] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8};

var array2 = new[] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8};

// Part 1: the way we do it normally

var result1 = new int[array1.Length];

for (var i = 0; i < result1.Length; i++)

{

result1[i] = array1[i] + array2[i];

}

// Part 2: trying to do the same thing, but with vectors

var result2 = new int[array1.Length];

var vectorA = new Vector<int>(array1);

var vectorB = new Vector<int>(array2);

(vectorA + vectorB).CopyTo(result2);If we open the assembly code produced by the first part, we can see that we loop over the following instructions 8 times (I omitted the loop instructions for clarity):

mov r9d, dword ptr [...] ; obtaining a value from array1

mov r10d, dword ptr [...] ; obtaining a value from array2

add r9d, r10d ; perform addition on two values

mov dword, ptr [...] ; save the result to result1While for the second part we only have:

vmovdqu ymm0, ymmword ptr ; load array1 into the first vector

vmovdqu ymm1, ymmword ptr ; load array2 into the second vector

vpaddd ymm0, ymm0, ymm1 ; perform addition on two vectors

vmovdqu ymmword ptr [...], ymm0 ; copy the vector to the arraySo, we just replaced a loop that repeats a bunch of instructions 8 times with just a few instructions. Hence, the name “single instruction, multiple data” and also that’s why sometimes people call vectorized computations “parallelization on a single processor”.

Vector Solution

Coming back to our problem with the knowledge we obtained, let’s write a new method that uses vectors:

public static int SimdSum(int[] array)

{

var sumVector = Vector<int>.Zero;

var i = 0;

for (; i <= array.Length - Vector<int>.Count; i += Vector<int>.Count)

{

sumVector += new Vector<int>(array, i);

}

var sum = 0;

for (var j = 0; j < Vector<int>.Count; j++)

{

sum += sumVector[j];

}

for (; i < array.Length; i++)

{

sum += array[i];

}

return sum;

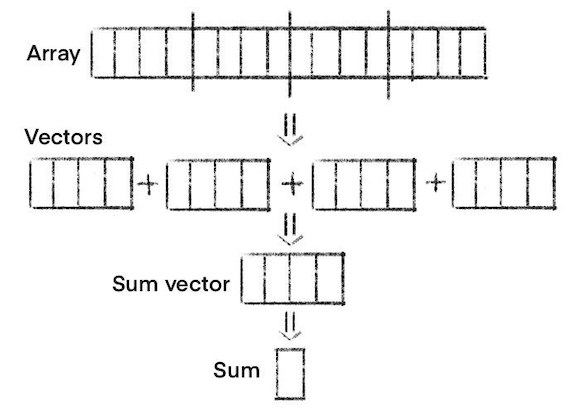

}Here we do a couple of things to split processing into vectors:

- We create a vectorized result containing all zeros. Since it’s a vector of integers, its size is 8.

- We go through our input array vector by vector, adding each vector to the result.

- Then we summarize all the elements residing in the vector result into a scalar integer result.

- Since our input array can have a length not divided evenly by the vector size, we have to deal with the remaining elements. We just add each element to the final result.

Let’s compare methods that we wrote so far trying to find a sum of an array of 1 million integers each having a value from 1 to 1000 (as always I use BenchmarkDotNet). I also included the LINQ-based method array.Sum() for the sake of comparison:

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev |

|--------- |------------:|----------:|----------:|

| LinqSum | 4,583.39 us | 21.706 us | 20.304 us |

| NaiveSum | 484.02 us | 3.759 us | 3.332 us |

| SimdSum | 81.87 us | 1.568 us | 1.743 us |The spec I ran this benchmark under:

- macOS 10.15.2

- Intel Core i7-8569U CPU 2.80GHz (Coffee Lake)

- .NET Core SDK=3.1.100

Bear in mind, though, we compare methods, one of which is CPU-dependent, so your result might be very different.

Conclusion

We might use a really simple problem as an example to explore vectorized computation, but even in this case, the final result is quite surprising. Of course, not all algorithms can use vectorization to speed things up. But even if you use the one that can, please always measure your performance before doing any tweaks.

You can check out code from this post on GitHub: VectorizedComputationsAndSimd.