Sparse Sets and Where to Find Them

Some time ago, while investigating sudden spikes in memory usage, I noticed a particular piece of code that was the culprit. Due to various obligations, I can’t mention any details or specifics, but in an overly simplified form, it went something like this:

foreach (var result in results)

{

var cache = new Dictionary<int, double>(MaxCapacity);

foreach (var item in result.Items)

{

// working with the cache reading from and writing data to it

// using the indexer, TryGetValue, and ContainsKey

}

}Although the code works correctly, it creates as many dictionaries as there are elements in results, putting pressure on garbage collection. While the .NET garbage collector is highly optimized these days, this approach is very inefficient and just doesn’t look right. Clearly, someone (it may or may not be the author of this post) made a mistake. What was likely intended was to move the dictionary outside of the outer loop and call Clear at the end:

var cache = new Dictionary<int, double>(MaxCapacity);

foreach (var result in results)

{

foreach (var item in result.Items)

{

// working with the cache reading from and writing data to it

// using the indexer, TryGetValue, and ContainsKey

}

cache.Clear();

}Not a significant change code-wise, but a huge difference in memory allocations:

| Method | Results | Mean | Error | StdDev | Allocated |

|----------------- |-------- |-------------:|-----------:|-----------:|--------------:|

| InnerDictionary | 1_000 | 14.903 ms | 0.2934 ms | 0.3493 ms | 30289.07 KB |

| OuterDictionary | 1_000 | 13.283 ms | 0.1285 ms | 0.1073 ms | 30.29 KB |

| InnerDictionary | 10_000 | 144.495 ms | 2.8604 ms | 4.1928 ms | 302890.72 KB |

| OuterDictionary | 10_000 | 131.527 ms | 2.2954 ms | 1.9168 ms | 30.39 KB |

| InnerDictionary | 100_000 | 1,483.173 ms | 29.4955 ms | 30.2897 ms | 3028906.64 KB |

| OuterDictionary | 100_000 | 1,300.657 ms | 14.0472 ms | 12.4525 ms | 30.68 KB |In the benchmarks, I’m using a simple code snippet that artificially emulates the problem and my regular rig:

- BenchmarkDotNet v0.13.12, Windows 11 (10.0.22631.3880/23H2/2023Update/SunValley3)

- Intel Core i7-10750H CPU 2.60GHz, 1 CPU, 12 logical and 6 physical cores

- .NET SDK 8.0.303, .NET 8.0.7

Not only did we significantly decrease memory allocation, we also slightly reduced the time.

Speaking of time, though, if we take a look at the Remarks section of the dictionary documentation, we find an interesting fact about the Clear method:

This method is an

O(n)operation, wherenis the capacity of the dictionary.

Considering the number of elements in results, let’s call m, and multiplying it by the number of key-value pairs in the cache, n, we get O(m*n) complexity just for clearing the dictionary. Well, apparently, the overhead of clearing is marginally better than creating a new dictionary each time we need it. However, this led me down a rabbit hole to see if we could get rid of this overhead to further decrease the time while keeping memory usage proportional to the cache size. It turns out we can. In this post, we’ll explore sparse sets, consulting with Russ Cox’s article, Using Uninitialized Memory for Fun and Profit, and see if they can help us with this problem.

Sparse Sets

If you’ve ever worked with dictionaries (or maps, as they’re called in some languages), you probably know they are based on hash tables. To put it simply, they use a hash function to compute a hash code from a key. This hash code then serves as an index pointing to a location in an array where the value is stored. The better the hash function, the more evenly distributed within the array the hash codes will be. Since the key space is usually much larger than the array size, different keys can produce the same hash code, resulting in a collision. Various collision resolution techniques exist to handle these scenarios. For example, an array’s item could store buckets or slots for multiple values instead of a single scalar value.

However, using hash tables and hash functions is not the only way to design a map. In certain cases, when the key space is known and relatively small, say, a 32-bit integer like in our problem, the overhead of hashing and resolving collision conflicts can be removed, and fast index lookups can be used instead. However, if we were to use regular arrays to store values with indexes serving as keys, we would be back to square one with the linear time for clearing the dictionary. So, what should we do? This is where sparse sets, an idea that has been around since the 1970s, come to the rescue.

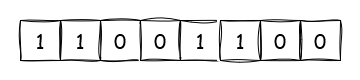

When it comes to a set of integers, one of the most popular implementations is a bit array, where each integer is represented by its index within the array. Initially, the array is filled with 0s or unset bits, indicating that it’s empty. To determine if the set contains an integer, we look up the corresponding index and check the bit. Similarly, to add an integer to the set, we simply set the bit. The following picture shows that we have added the numbers 0, 4, 5, and 1 to the set:

The bit array works well until we need to perform two operations: iteration and clearing. In both cases, the time is linear relative to the number of elements in the array. If the array is sparsely populated, meaning it has large gaps between set bits, we would spend quite a while going over unset bits that aren’t very interesting to us.

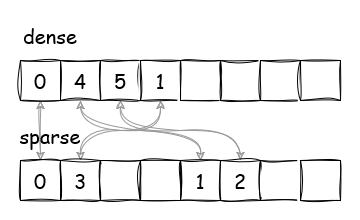

Let’s try to represent it differently as a packed array of integers instead. In our example, we pack the bit array, replacing 1s with the actual indexes, and can call it dense. By doing so, we go from an array containing 8 bits to an array containing 4 integers:

Looks good now. We can reconstruct the set using this new array and knowing how many elements we added. However, we lose efficiency in read operations, because now we need to go through the array in order to check if the set contains an item. This is where the second array comes into play. We add a new array called sparse, which contains indexes pointing to the elements in dense at the corresponding positions. Essentially, we create two arrays whose elements are pointing to each other:

As we add items to the set and keep track of the position of a newly added element in dense, we can see that read, write, iterate, and clear operations become highly efficient. Adding a new item to the set or retrieving an item from the set is as simple as doing two lookups. Iterating over all items is equivalent to iterating over dense until we hit the position of the most recently added element. Clearing the set is just resetting the position to 0.

Notice that once we clear the set, resetting the position to 0, we don’t actually do anything with either dense or sparse. They can have any arbitrary value, and yet the set still works correctly. The trick is that we only check the element in dense when we do the key lookup in sparse, verifying the element’s position and checking its value against dense. We will see how it works in code in a moment.

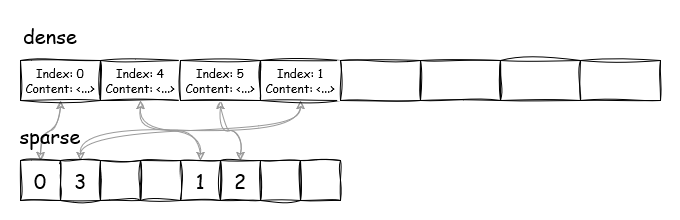

We can take this idea of sparse sets further and apply it to dictionaries, as from a programmer’s perspective, dictionaries are essentially sets with values attached. So the dense array from above would look like this:

Now, let’s jump into a code editor and implement SparseDictionary. Since we are only working with our well-defined problem, we won’t go full on the drop-in Dictionary<TKey, TValue> replacement, but instead work through a relatively small subset of the Dictionary that only has methods we need.

SparseDictionary

First, since we want to store not only the keys but also the values, we need to define a class that would store the pair:

internal class Item<T>

{

public int Key;

public T? Value;

}Next, we can proceed with dense and sparse arrays by creating the dictionary class to manage them. The class would have the arrays, _dense and _sparse, and _position to keep track of the position of the most recently added element to _dense. Since we do care about the size of the arrays, we also need to add a constructor accepting size that initializes them:

public class SparseDictionary<T>

{

private readonly Item<T>[] _dense;

private readonly int[] _sparse;

private int _position;

public SparseDictionary(int size)

{

_dense = new Item<T>[size];

_sparse = new int[size];

for (var i = 0; i < size; i++)

{

_dense[i] = new Item<T>();

}

}

}With this setup, we can see that implementing Count and Capacity to get the number of elements and the dictionary’s maximum capacity, respectively, is as easy as exposing a few fields via properties:

public int Capacity => _sparse.Length;

public int Count => _position;The most interesting part, perhaps, would be the indexer:

public T this[int key]

{

get

{

if (key < 0 || key >= _sparse.Length)

{

throw new IndexOutOfRangeException($"Key {key} is out of range 0..{_sparse.Length}");

}

if (!TryGetIndex(key, out var index))

{

throw new KeyNotFoundException($"Key {key} is not found");

}

return _dense[index].Value!;

}

set

{

if (key < 0 || key >= _sparse.Length) // (1)

{

throw new IndexOutOfRangeException($"Key {key} is out of range 0..{_sparse.Length}");

}

if (TryGetIndex(key, out var index)) // (2)

{

_dense[index].Value = value;

return;

}

_dense[_position].Key = key; // (3)

_dense[_position].Value = value;

_sparse[key] = _position;

_position++; // (4)

}

}

private bool TryGetIndex(int key, out int index)

{

index = _sparse[key];

return index < _position && _dense[index].Key == key;

}For the getter part, we need to check the key boundaries first, and if it’s out of bounds, we throw an IndexOutOfRangeException. Next, we check the key’s index with the TryGetIndex helper method, this is where the sparse set trick comes into play. Since we already verified that the key is in range, we look up its dense index in the _sparse array and return it as index. Then we check if the index fits into _position and if the actual key we store in _dense matches the key. If none of this is true, we throw a KeyNotFoundException. But if it is true, we got the index, thus being able to return index’s value part of the item.

The setter part might need a bit more explaining, so let’s break it down:

- First things first, we have to check the

key’s range again. - Then we do the same

keyverification we did in the getter part. Here, however, if the key is found, we just update theValuepart of the stored item, and return from the method. - Otherwise, we update the

Itemat the current position withkeyandvalue, and also update the sparse array with its_position. - Finally, we increment

_position.

We might also want to add two more methods often used in dictionaries, ContainsKey, TryGetValue, and Remove:

public bool ContainsKey(int key)

{

return key > 0 && key < _sparse.Length && TryGetIndex(key, out _);

}

public bool TryGetValue(int key, [NotNullWhen(true)] out T? value)

{

if (key < 0 || key >= _sparse.Length || !TryGetIndex(key, out var index))

{

value = default;

return false;

}

value = _dense[index].Value!;

return true;

}

public void Remove(int key)

{

if (!TryGetIndex(key, out var index)) return;

var last = _dense[_position - 1];

_dense[index] = last;

_sparse[last.Key] = _sparse[key];

_position--;

}The first two look somewhat similar to the getter, except that they return false instead of throwing IndexOutOfRangeException and KeyNotFoundException. To implement Remove we just need to verify that the key exists, place the last item on its place, and decrease _position.

Last but not least, we need a method to clear the dictionary. You’ve probably guessed by now what it looks like:

public void Clear()

{

_position = 0;

}That’s it, we only need to set _position to 0.

Now if we compare the results, we can see that we managed to slash even more time:

| Method | Results | Mean | Error | StdDev | Allocated |

|----------------- |-------- |-------------:|-----------:|-----------:|--------------:|

| InnerDictionary | 1_000 | 14.118 ms | 0.0981 ms | 0.0819 ms | 30289.07 KB |

| OuterDictionary | 1_000 | 13.387 ms | 0.2639 ms | 0.3142 ms | 30.29 KB |

| SparseDictionary | 1_000 | 9.222 ms | 0.0356 ms | 0.0316 ms | 43.06 KB |

| InnerDictionary | 10_000 | 138.398 ms | 1.2573 ms | 1.1761 ms | 302890.72 KB |

| OuterDictionary | 10_000 | 128.411 ms | 2.2158 ms | 2.0727 ms | 30.39 KB |

| SparseDictionary | 10_000 | 94.332 ms | 1.0138 ms | 0.8987 ms | 43.12 KB |

| InnerDictionary | 100_000 | 1,471.180 ms | 29.3344 ms | 27.4394 ms | 3028906.64 KB |

| OuterDictionary | 100_000 | 1,279.040 ms | 11.9458 ms | 9.9753 ms | 30.68 KB |

| SparseDictionary | 100_000 | 976.444 ms | 16.2609 ms | 15.2105 ms | 43.45 KB |Neat. We have traded a bit more memory to save roughly 20% of time.

It’s all fine and dandy, but in our particular problem, we don’t iterate over the dictionary. We didn’t even implement iteration in SparseDictionary. Which poses a question: if we don’t really need iteration, can we sacrifice it to gain some performance for reads and writes? The answer is yes: with a bit of a change, we can transform the dictionary based on the sparse set into a dictionary based on generations.

GenerationDictionary

It turns out that I was not the only one looking in the same direction; Iskander Sharipov also explored this idea in his interesting article, Generations-based array, which explains how we can improve read and write performance by giving up on iteration’s speed. The article does an excellent job of explaining the inner workings behind the approach, so I won’t go into detail here.

The core idea behind this approach is that, since we use integers as keys, we can store items in one array rather than in a sparse-dense combination. However, to achieve constant time complexity for clearing the dictionary, we use a notion of generations. The dictionary has a generation number, which is assigned to each item when it is added. Every time we read from the dictionary, we check if the dictionary’s generation matches the item’s generation. When the dictionary is cleared, we simply increment the generation number. Quite elegant, isn’t it?

The code in the article is written in Go, so let’s port it to C#, starting with the Item class:

internal class Item<T>

{

public int Generation;

public T? Value;

}We only need two fields for the item: the Generation and the Value itself. By default, they are 0 and null, respectively. Next stop, we create the dictionary class:

public class GenerationDictionary<T>

{

private int _generation = 1;

private int _count = 0;

private readonly Item<T>[] _items;

public GenerationDictionary(int size)

{

_items = new Item<T>[size];

for (var i = 0; i < size; i++)

{

_items[i] = new Item<T>();

}

}

}Here we define dictionary’s _generation, which is set to 1 to indicate that it contains no items, the number of items _count, and _items that actually stores the items. We also need a constructor that takes in the size of the dictionary to initialize the _items array.

Similarly to SparseDictionary, we can easily add Capacity and Count methods:

public int Capacity => _items.Length;

public int Count => _count;The indexer, however, would look a bit differently from the previous version:

public T this[int key]

{

get

{

if (key < 0 || key >= _items.Length)

{

throw new IndexOutOfRangeException($"Key {key} is out of range 0..{_items.Length}");

}

var item = _items[key];

if (item.Generation != _generation)

{

throw new KeyNotFoundException($"Key {key} is not found");

}

return item.Value!;

}

set

{

if (key < 0 || key >= _items.Length)

{

throw new IndexOutOfRangeException($"Key {key} is out of range 0..{_items.Length}");

}

_items[key].Generation = _generation;

_items[key].Value = value;

_count++;

}

}For the getter part, we first check if the key is within range; if not, we throw an IndexOutOfRangeException. Then, we retrieve the item using the key and check its Generation: if it doesn’t match the dictionary’s _generation, we throw a KeyNotFoundException. Otherwise, we return its value.

The setter part becomes even more straightforward in this implementation. First, we do the same check as in the getter. Then, we simply update the item’s Generation and Value, remembering to also increment _count.

Next, let’s implement the methods we added to SparseDictionary: ContainsKey, TryGetValue, and Remove:

public bool ContainsKey(int key)

{

if (key < 0 || key >= _items.Length) return false;

return _items[key].Generation == _generation;

}

public bool TryGetValue(int key, [NotNullWhen(true)] out T? value)

{

if (key < 0 || key >= _items.Length)

{

value = default;

return false;

}

var item = _items[key];

if (item.Generation != _generation)

{

value = default;

return false;

}

value = item.Value!;

return true;

}

public void Remove(int key)

{

if (key < 0 || key >= _items.Length) return;

var item = _items[key];

if (item.Generation != _generation) return;

_items[key].Generation = 0;

_count--;

}Much like in SparseDictionary, the first two methods are very similar to the getter, but they return false instead of throwing exceptions. For the Remove method, we need to check the key and the item’s Generation, and set the Generation to 0 to indicate that the item is no longer present in the dictionary. We must also decrement _count.

Finally, the Clear method is slightly more complex than its counterpart from SparseDictionary, but this complexity comes only because we need to be cautious with an integer overflow:

public void Clear()

{

_count = 0;

if (_generation < int.MaxValue)

{

_generation++;

return;

}

_generation = 1;

for (var i = 0; i <_items.Length; i++)

{

_items[i].Generation = 0;

}

}Here we first set _count to 0 and then check if _generation has reached int.MaxValue. If it’s below the maximum value, we simply increment _generation and return. Otherwise, we must iterate over all items and explicitly set their Generation to 0. Although this implementation technically iterates over all items during clearing, it only occurs once every 2 147 483 647 times, which is not that bad, if you ask me.

Now, let’s add one more benchmark to the list and see if we gained any benefits for all these hassles:

| Method | Results | Mean | Error | StdDev | Allocated |

|--------------------- |-------- |-------------:|-----------:|-----------:|--------------:|

| InnerDictionary | 1000 | 14.391 ms | 0.2778 ms | 0.3199 ms | 30289.07 KB |

| OuterDictionary | 1000 | 12.978 ms | 0.2481 ms | 0.2437 ms | 30.29 KB |

| SparseDictionary | 1000 | 9.399 ms | 0.1531 ms | 0.1432 ms | 43.06 KB |

| GenerationDictionary | 1000 | 6.990 ms | 0.1262 ms | 0.1181 ms | 39.12 KB |

| InnerDictionary | 10000 | 143.160 ms | 2.1777 ms | 1.9305 ms | 302890.72 KB |

| OuterDictionary | 10000 | 132.859 ms | 2.1741 ms | 1.9273 ms | 30.39 KB |

| SparseDictionary | 10000 | 95.613 ms | 1.4979 ms | 1.4012 ms | 43.13 KB |

| GenerationDictionary | 10000 | 73.540 ms | 1.4682 ms | 2.6098 ms | 39.17 KB |

| InnerDictionary | 100000 | 1,469.565 ms | 18.4316 ms | 17.2409 ms | 3028906.64 KB |

| OuterDictionary | 100000 | 1,284.033 ms | 24.5744 ms | 30.1796 ms | 30.68 KB |

| SparseDictionary | 100000 | 981.956 ms | 19.0033 ms | 17.7757 ms | 43.45 KB |

| GenerationDictionary | 100000 | 744.494 ms | 14.0887 ms | 14.4680 ms | 39.51 KB |As it turns out, we did. In addition to time reduction we also saved a bit more memory due to using only one array.

Conclusion

Of course, SparseDictionary or GenerationDictionary can’t serve as a drop-in replacement for the regular Dictionary. The built-in class is way more versatile, highly optimized, and covers a wide range of use cases. However, there may be situations, as mentioned at the beginning of the post, where alternatives like the ones we explored in this post could be considered.

As it often happens in software development, even teeny-weeny problems like this rarely have clear-cut solutions, instead they have trade-offs. It is, however, good to know that there are various options to choose from. Once again, the old saying holds true: don’t trust someone else’s benchmarks, rely on your own performance measurements.

You can check out the code from this post on GitHub: SparseSets.