Breaching Breach Protocol

As someone who grew up watching The Matrix, Johnny Mnemonic, RoboCop and reading books by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, it’s no wonder I loved Cyberpunk 2077, a 2020 action-adventure game by CD Project Red. In addition to the engaging story, gorgeous soundtrack, and its many other merits, Cyberpunk 2077 has an interesting mini-game nicely incorporated into the game world — Breach Protocol. Each time a player needs to perform a device hack using Breach Protocol, the mini-game interface opens up:

The rules of the game are simple. On the left side, there’s a code matrix containing elements 1C, 55, 7A, BD, E9, and FF. On the right side, we have a list of sequences, each consisting of elements from the same set. All we need to do is to pick elements from the matrix one by one and place them into the buffer in the correct order to compose one or more sequences shown on the right side. As soon as we have a completed sequence in the buffer, it’s considered uploaded. We start with the first row of the matrix, but each time we find a matching element, the game alters the row/column direction. Every uploaded sequence gives us a reward assigned to it.

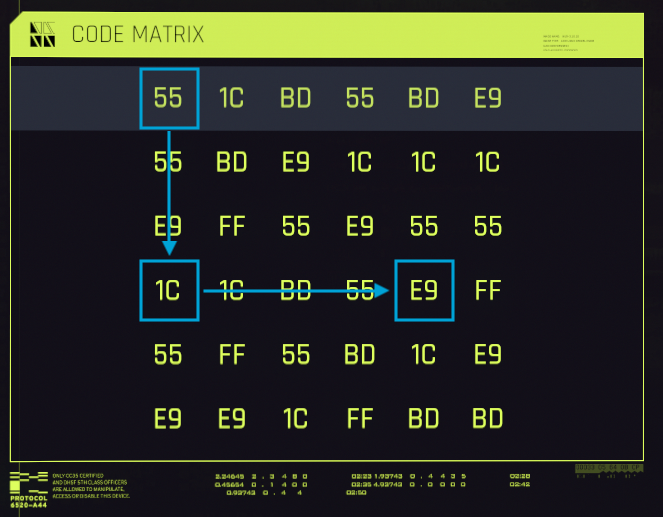

On the screenshot, we have two sequences containing 4 and 3 elements, respectively, and a buffer size of 6. Say, we want to upload the first sequence. There is more than one way to do this, but as an example, we can pick the elements like that:

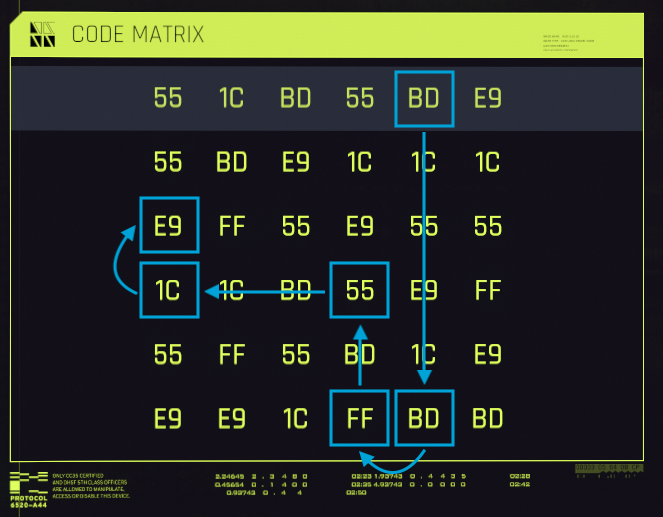

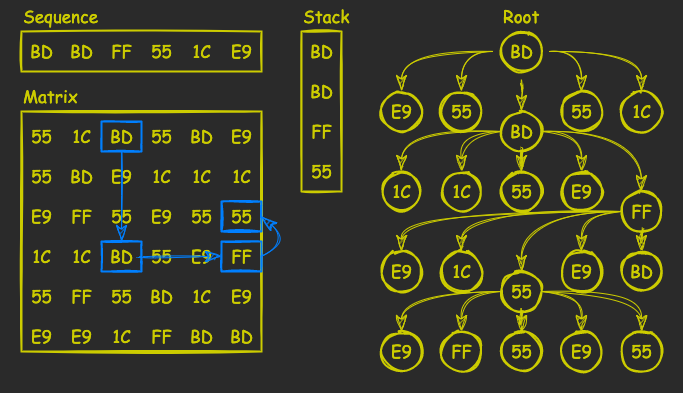

We could concatenate two sequences together and upload a combined sequence containing 7 elements, had we had enough buffer space. However, since the last element of the second sequence matches the first element of the first sequence, we can actually chain them together into one that would still fit into the buffer: BD BD FF 55 1C E9. Now, we can pick all its elements from the matrix:

Hooray, we just uploaded both sequences and got two rewards. Sweet!

This mini-game is definitely not rocket science, but naturally a curious mind starts to wonder if its possible to write a program that would solve Breach Protocol automatically based on the matrix, list of sequences, and buffer size. Surely enough, it’s possible, and such solvers exist in abundance. Just to name the two popular ones: Cyberpunk 2077 Hacking Minigame Solver by Joona Heikkilä or Optical Breacher by govizlora. The latter is even capable of doing image recognition to read the input data automatically.

Most of the solvers — at least the ones I had a look at — use brute-force of some sorts to crack the puzzle. If you’re like me, wondering if it’s possible to use another approach, let’s grab an algorithm cookbook, open our favorite text editor, and dive in jack in.

Analysis

If we squint hard enough, we’ll see that there’re actually two problems behind solving Breach Protocol.

First, we need to decide what sequence or chained combination of sequences we want to upload to the buffer. Unlike our example above, it’s not always possible to chain all sequences together and place them into the buffer. The buffer might not have enough space, a longer sequence might not exist in the code matrix, or, for some reason, the player might not want to upload certain sequences. As each sequence has a certain reward, we can’t decide for the player what reward they want to get, so we will delegate the decision to them.

Now that the player is responsible for managing sequences and their combinations, we can concentrate on the second problem: finding the desired sequence in the matrix.

Despite the problem’s solution appearing as a matrix traversal, we can actually represent it as traversing a tree. Which will come in handy as we could apply a version of depth-first search (or DFS for short) slightly modified for the game’s rules. Let’s break it down step by step:

- First thing we need is to find the root of the tree — the first element of the sequence. Since it’s not guaranteed that the first row we start with contains it, we have to scan the whole matrix.

- Once found, we recursively run DFS on the element:

- we push the element onto the stack

- then we compare the stack’s length against the sequence’s length — that’s our termination condition — if they’re equal, we exit DFS

- otherwise, we scan the row/column looking for the next sequence element (we can think of the row/column elements as root’s children)

- if we have a match, we run DFS on the element, altering the direction

- Once we exit DFS, we see if the algorithm gave us a desired result stored in the stack. If the root was not found in the first row, we would need to add another element from the first row — the game rules dictate that the solution has to start with the first row’s element regardless.

- If DFS doesn’t give us the result, we continue scanning the matrix, looking for another root.

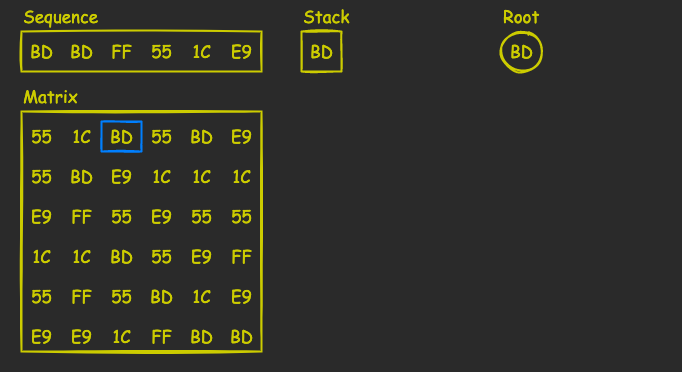

Let’s see how the algorithm works by running it on our example from above. The sequence we want to upload is BD BD FF 55 1C E9, so we have to scan the matrix for the first occurrence of BD, push it onto the stack, and make it a root of the tree:

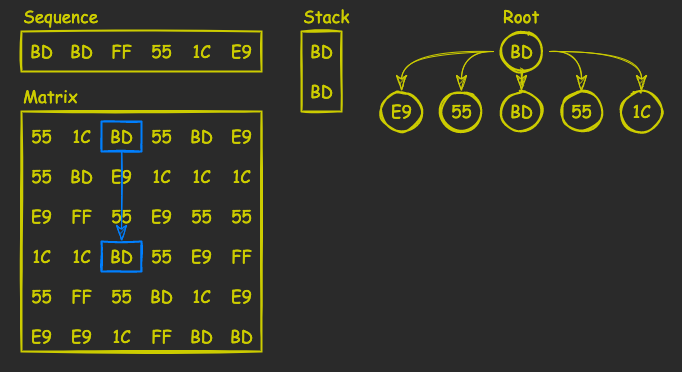

Then we alter the direction, scan the column representing its elements as root’s children (excluding the root element, of course), and look for the second element in the sequence, BD. Once found, we push it onto the stack:

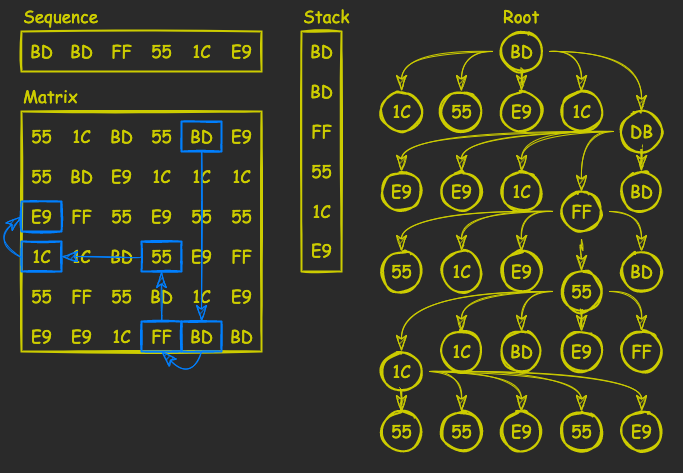

Next, we repeat the process until we find all the elements. If we are unlucky, though, we reach a situation in which a row/column doesn’t contain a matching element. See the example on the picture below: we are now searching for 1C, but the row, containing a previously found 55, doesn’t have it:

In this case, we pop the stack and try other elements. If we fail to find all sequence elements in the tree, we abandon this particular root and continue scanning the matrix for the next one.

Eventually, if the sequence does exist in the matrix, we will have all its elements in the stack:

Implementation

You have probably noticed that values of the matrix and sequence are just bytes written in hex, so 1C is 28, 55 — 85, 7A — 122, BD — 189, E9 — 233, and FF is 255. Since we are going to implement the algorithm in Go, we can encode them as bytes. The sequence, then, becomes a byte slice []byte, and the matrix — a slice of byte slices [][]byte.

The result of the algorithms is a list of sequence elements’ indexes. We can encode an index using the following struct:

type Point struct {

X, Y int

}Which gives us the algorithm’s return type []Point.

Last but not least, Go doesn’t have a built-in stack implementation, so we have to write a poor man’s stack ourselves.

Stack

The only thing our stack actually needs is a backing slice to store points:

type stack struct {

storage []Point

}Since we won’t use this stack outside the package, we make it private. Which also allows us to take some liberty in designing an API we want. Speaking of which, let’s introduce methods to manipulate data on the stack, push and pop:

func (s *stack) push(p Point) {

s.storage = append(s.storage, p)

}

func (s *stack) pop() {

if len(s.storage) == 0 {

return

}

s.storage = s.storage[:len(s.storage)-1]

}I guess both don’t require any explanation. Just one little detail: when using pop in the algorithm, we don’t actually need a popped value, so it returns nothing. That also makes our life easier in case of an empty stack — we just return from the method, doing nothing.

Let’s also add a couple of additional methods:

func (s *stack) len() int {

return len(s.storage)

}

func (s *stack) exists(p Point) bool {

for _, v := range s.storage {

if v == p {

return true

}

}

return false

}

func (s *stack) slice() []Point {

return s.storage

}All three are really obvious: len just returns the length of the backing slice, exists checks if a point exists in the storage, and slice returns the content of the backing slice. If you smell a leaky abstraction in the last method and are about to call the OOP police, you’re absolutely right: we expose an underlying structure without any protection whatsoever, allowing the caller to manipulate its data directly. If we were to write a public API, we’d of course make a new slice, copy all the points, and return it to the caller. However, we’re writing a private implementation that’s going to be used in our package only, so it’s a safe space, we are all friends here. Let’s leave it like that, but maybe don’t try it at home.

Solver

Now that we have the stack, we can introduce the Solve function that accepts the matrix and the sequence we defined above:

func Solve(matrix [][]byte, seq []byte) []Point {

s := stack{}

for i := 0; i < len(matrix); i++ {

for j := 0; j < len(matrix[0]); j++ {

if matrix[i][j] == seq[0] {

dfs(matrix, seq, &s, Point{i, j}, i != 0)

if s.len() == len(seq) {

if i != 0 {

return append([]Point{%raw%}{{0, j}}{%endraw%}, s.slice()...)

}

return s.slice()

}

}

}

}

return s.slice()

}In the function, we just follow the algorithm described in the Analysis section. We create the stack and scan the matrix looking for the first element of the sequence, that’s going to be the root of the tree. Once found, we run DFS on it and check the stack’s length: if it matches the seq’s length, we return its backing slice, otherwise, we continue scanning the matrix. Since it’s not guaranteed that the first element of seq will lie in the first row (and according to the rules, we have to start with the first row regardless), we need to account for that by supplying an additional element from the first row to the beginning of the returning slice.

Finally, we need to implement DFS providing the matrix, seq, a pointer to the stack s, the tree root p, and direction dir which takes true if it’s going row-wise and false for column-wise:

func dfs(matrix [][]byte, seq []byte, s *stack, p Point, dir bool) {

s.push(p)

if s.len() == len(seq) {

return

}

if dir {

for i := 0; i < len(matrix[0]); i++ {

candidate := Point{p.X, i}

if s.len() < len(seq) && matrix[p.X][i] == seq[s.len()] && !s.exists(candidate) {

dfs(matrix, seq, s, candidate, false)

}

}

} else {

for i := 0; i < len(matrix); i++ {

candidate := Point{i, p.Y}

if s.len() < len(seq) && matrix[i][p.Y] == seq[s.len()] && !s.exists(candidate) {

dfs(matrix, seq, s, candidate, true)

}

}

}

if s.len() < len(seq) {

s.pop()

}

}We start by pushing p onto the stack and checking the stack’s length. If it’s equal to seq’s length, the stack contains the whole sequence, and we exit the function. Otherwise, depending on the direction, we check if row/column elements match the next seq element. If so, we run DFS on the point representing the element. At the very end we check the stack length again: if it’s less than seq’s length, that means we took the wrong path, so we pop the stack and move on to the next path.

And that’s the whole thing. Of course, we’ve cheated a bit by offloading some work, such as selecting a sequence to upload, to the player. So it won’t be fair to compare this implementation to full-fledged solvers, such as the ones I linked to at the beginning of the post. However, it’s definitely a different approach that might be worth looking at. So, I’m going to leave it like that and go do a few gigs in Night City.

You can check out the code from this post on GitHub: breach.